When a task must be performed by a group rather than an individual, the problem of working relationships arises. For entire classes of tasks success depends upon an effective flow of information. Do structural properties limit group performance? What effects can [the structure] have upon the emergence of leadership, the development of organization, the degree of resistance to group disruption, the ability to adapt successfully to sudden changes in the working environment? BAVELAS,

Alex, 1950. Communication Patterns in Task‐Oriented Groups. The Journal

of the Acoustical Society of America. November 1950. Vol. 22,

no. 6, p. 725–730. DOI 10.1121/1.1906679. doi ![]()

Ralf Barkow suggested this paper in September 2022 in response to Reliability and Complexity via matrix ![]()

If we consider a task-group in terms of who can communicate with whom, without regard for the nature of communication, we can ask a number of simple but important questions. Let us vary the way in which five individuals are linked to each other.

graph { subgraph cluster_a { A [penwidth=0] A -- a1 [style=invis] a1 -- a2 -- a3 -- a4 -- a5 -- a1 } subgraph cluster_b { B [penwidth=0] B -- b1 [style=invis] b1 -- b2 -- b3 -- b4 -- b5 } subgraph cluster_c { C [penwidth=0] C -- c1 [style=invis] c1 -- c2 -- { c3 c4 c5} } subgraph cluster_d { D [penwidth=0] D -- d1 [style=invis] d1 -- { d2 d3 d4 d5} } }

Students often remark, upon seeing these patterns for the first time, that D is "autocratic," whereas pattern C is a typical "business set-up." Actually the linkages are identical, the only difference being the arrangement of the circles in the drawing. There are some real differences between A, B, and C, however.

Let us turn now to the question of how these patterns might be used by a group...in terms of some specified task. Each individual is dealt five playing cards from a normal poker deck. The group is to construct the best poker hand using one card from each individual. Each may only send messages to individuals along the linkages.

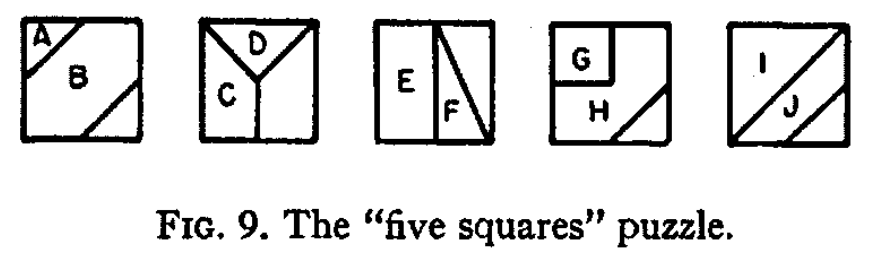

Figure 9. The "five squares" puzzle.

[Another] task consists essentially of forming squares from various geometric shapes. In Figure 9 are shown the pieces that make up the puzzle and how they go together to form five squares.

Out of these shapes, squares may be made in many ways. Some of the possible combinations are: CCAA, EAAAA, EAAG, FFAAAA, FFCA, FFGAA, ICA. However, if five squares must be constructed out of the fifteen pieces, there is only one arrangement that can succeed. In the experimental situation... messages and pieces may be passed along open channels.

In preliminary trials the wrong squares appear with great regularity. The point of the experiment is what happens once these failure "successes" occur. For an individual who has completed a square, it is understandably difficult to tear it apart. The ease with which he can take a course of action away from his goal should depend to some extent upon his perception of the total situation. In this regard, the pattern of communication should have well-defined effects.